Por Anthony J. Brown

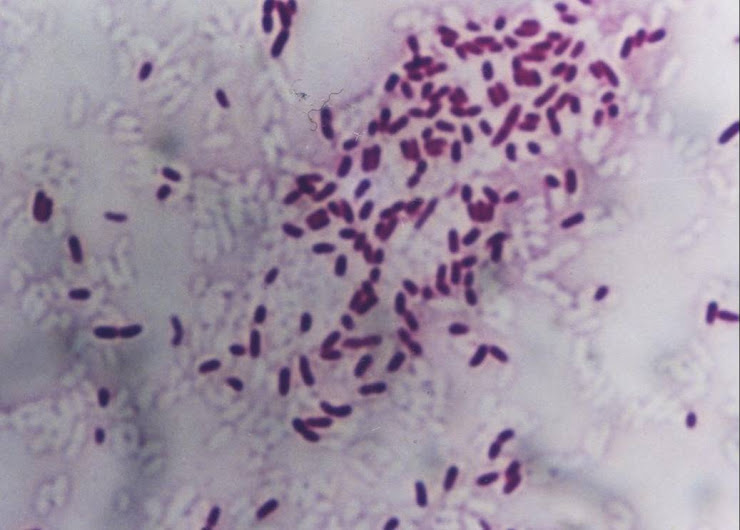

NUEVA YORK (Reuters Health) - El "supergermen" mortal, resistente a los fármacos, Staphylococcus aureus resistente a la meticilina (SARM) puede sobrevivir por semanas o meses en los juguetes y en otros objetos inanimados, lo que eleva el riesgo de transmisión a la piel.

El SARM fue un gran problema en los hospitales, porque atacaba a los pacientes debilitados por una enfermedad. Pero brotes recientes en la comunidad en personas sanas generaron una nueva preocupación.

Estudios previos habían demostrado que el SARM puede permanecer en varios objetos del entorno, indicó a Reuters Health el autor principal del estudio, doctor Rishi Desai, de Childrens Hospital Los Angeles.

"Nuestro estudio va dos pasos más allá porque demuestra la cantidad exacta de la bacteria que se puede encontrar en el tiempo y que el supergermen no sólo sobrevive en el entorno, sino que se transmite a la piel durante períodos prolongados", agregó Desai.

"Los hallazgos principales fueron que el SARM en la comunidad puede sobrevivir y pasar a la piel durante dos meses cuando está en objetos plásticos, como el vinilo y los bloques plásticos de construcción que usan los niños", declaró.

Desai presentó los resultados en Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, esta semana, en San Francisco.

El equipo de Desai obtuvo varios objetos involucrados en brotes de SARM adquirido en la comunidad, los cortó en bloques de 2 x 2 centímetros cuadrados y los esterilizó.

Luego, colocó en cada objeto cantidades pequeñas de la cepa del SARM hallada en la comunidad. Los objetos permanecieron así durante distintos períodos. Cada tanto, el equipo presionó un trozo de piel de cerdo estéril sobre el objeto y analizó la presencia del supergermen.

El equipo halló que el SARM puede transmitirse durante períodos más prolongados desde las superficies no porosas, como bloques plásticos y vinilo, que de las superficies porosas, como las sábanas.

A diferencia de las cepas del SARM adquiridas en el hospital, el SARM en comunidad podría transmitirse desde objetos plásticos a la piel después de períodos más prolongados.

Un objeto no poroso (hojas de afeitar) no transmitió el SARM más allá de 5 minutos.

Las barras de jabón tampoco transmitieron el SARM a la piel.

A las personas con SARM adquirido en comunidad "se les debería recomendar mantener la limpieza del hogar, en especial las superficies no porosas", destacó Desai.

NUEVA YORK (Reuters Health) - El "supergermen" mortal, resistente a los fármacos, Staphylococcus aureus resistente a la meticilina (SARM) puede sobrevivir por semanas o meses en los juguetes y en otros objetos inanimados, lo que eleva el riesgo de transmisión a la piel.

El SARM fue un gran problema en los hospitales, porque atacaba a los pacientes debilitados por una enfermedad. Pero brotes recientes en la comunidad en personas sanas generaron una nueva preocupación.

Estudios previos habían demostrado que el SARM puede permanecer en varios objetos del entorno, indicó a Reuters Health el autor principal del estudio, doctor Rishi Desai, de Childrens Hospital Los Angeles.

"Nuestro estudio va dos pasos más allá porque demuestra la cantidad exacta de la bacteria que se puede encontrar en el tiempo y que el supergermen no sólo sobrevive en el entorno, sino que se transmite a la piel durante períodos prolongados", agregó Desai.

"Los hallazgos principales fueron que el SARM en la comunidad puede sobrevivir y pasar a la piel durante dos meses cuando está en objetos plásticos, como el vinilo y los bloques plásticos de construcción que usan los niños", declaró.

Desai presentó los resultados en Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, esta semana, en San Francisco.

El equipo de Desai obtuvo varios objetos involucrados en brotes de SARM adquirido en la comunidad, los cortó en bloques de 2 x 2 centímetros cuadrados y los esterilizó.

Luego, colocó en cada objeto cantidades pequeñas de la cepa del SARM hallada en la comunidad. Los objetos permanecieron así durante distintos períodos. Cada tanto, el equipo presionó un trozo de piel de cerdo estéril sobre el objeto y analizó la presencia del supergermen.

El equipo halló que el SARM puede transmitirse durante períodos más prolongados desde las superficies no porosas, como bloques plásticos y vinilo, que de las superficies porosas, como las sábanas.

A diferencia de las cepas del SARM adquiridas en el hospital, el SARM en comunidad podría transmitirse desde objetos plásticos a la piel después de períodos más prolongados.

Un objeto no poroso (hojas de afeitar) no transmitió el SARM más allá de 5 minutos.

Las barras de jabón tampoco transmitieron el SARM a la piel.

A las personas con SARM adquirido en comunidad "se les debería recomendar mantener la limpieza del hogar, en especial las superficies no porosas", destacó Desai.

"Sugerimos limpiar seguido las superficies en los hogares donde viven los pacientes con SARM adquirido en la comunidad para reducir el riesgo de diseminación de la infección al resto de la familia", agregó el autor.